Written by John Morris

Photographs courtesy of James “DOC” Radawski

Shipwreck Discoveries Could Change History Books

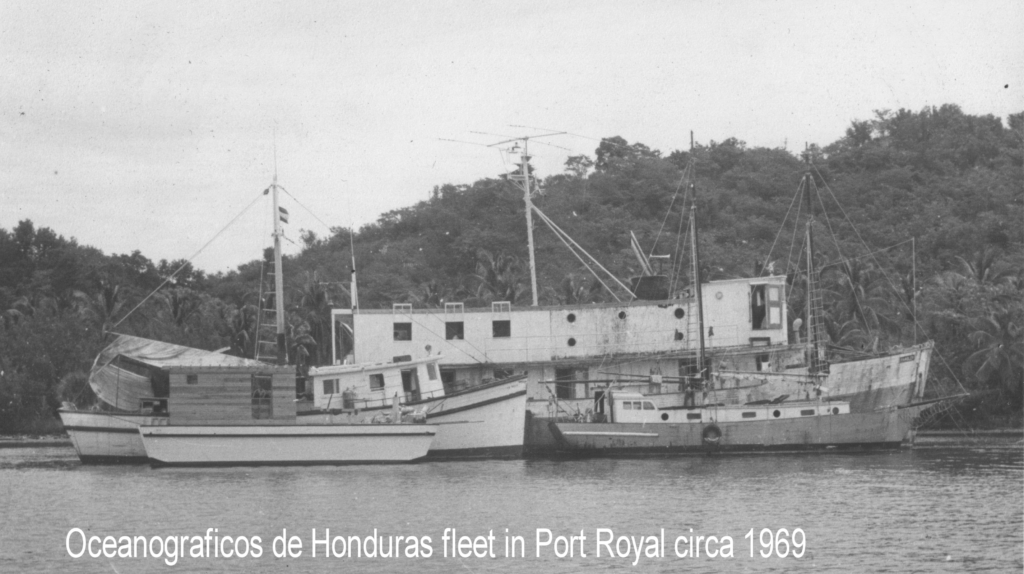

There are many shipwrecks in Roatan for diving, most intentionally sunk and strategically placed for accessibility and minimal disturbance to the world’s second largest barrier reef as well as additional reef creation. Yet with the island’s pirate and colonial conflict past, the possibility of much older wrecks is quite intriguing both for marine archeologists and for treasure hunters. Such was the case in 1968, when the Oceanograficos de Honduras was granted a permit from the Honduran government to explore such possibilities in the waters off Old Port Royal. What they found in the ensuing 5 years of exploration and excavation still to this day cannot be explained, and if it could be, history books would have to be rewritten.

The fascinating tales of treasure hunting by Mitchell Hedges and Howard Jennings in and around Old Port Royal are well documented and even remembered by those in the 80 to 100 year old age group still living in St Helene where both explorers paid for artifacts during their time here, yet they were strictly land and shallow water searchers, lacking the necessary equipment to dive for wrecks. The man who was to change that arrived on Roatan by accident. After logging over 15,000 nautical miles exploring both coasts of Central and South America for sunken treasure laden vessels on his 56 foot gaff-masted schooner, the Santa Maria, Captain Michael “Mick” Johnston, was in dire need of some dry dock repairs. While in Puerto Cortes, he was told that the only place nearby that could help him was in Oak Ridge on the island of Roatan, and thus, in 1965, the Santa Maria arrived in the Bay Islands and never left.

Though the necessary dry dock repairs needed were taken care of fairly quickly, the stories Mick heard from the locals sounded too good to be true and were too good not to investigate. Sunken galleons and British frigates were right in front of him and he knew he had to find them. A quick trip back to the United States to confirm Roatan’s colonial history cemented the deal and thus his unexpected odyssey to find what he had spent two years searching for began. First and foremost, to be sure of his safety, Mick knew he had to get a permit from the Honduran government to begin his search. Hedges and Jennings had already ruffled enough feathers and he did not want to take the chance to be seen in the same light, so he went to Tegucigalpa to learn what had to be done. It was 1967 and Honduras was under military rule. Strangely enough, the Ministry of Archeology was under the Ministry of Education which in turn was under the Ministry of Defense. Completely understanding the chain of command, Mick went to the top. Negotiations and agreements were made with the Honduran government as to the purpose and rules of this mission, listed below as presented in the paper submitted by Oceanograficos De Honduras at the 6th International Conference on Underwater Archeology in Charleston, South Carolina on January 7th 1975:

- It is legally established a scientific mission to perform marine archaeological work in the country.

2. Specific terms of the contract provide and insure that the work shall be done in accordance with good marine archaeological procedure.

3. A marine archaeological zone is established.

4. All artifacts recovered remain property of the government.

5. Fifty percent of the artifacts recovered are loaned back to the contracting marine archaeological organization. The objective of this provision is to provide for the preservation, study and display of the artifacts.

6. The contractor holds film and publication rights in return for providing governmental agencies with copies of published material.

7. The contractors have the concession to create an archaeological museum in Roatan to display the artifacts discovered.

8. The contractors may loan part of the collection to qualified foreign institutions with approval of the government.

9. Any material recovered which does not have archaeological or cultural value will be treated under the existing salvage laws of the country. Permit in hand, Mick needed help and posted a want ad back in his home of southern California for divers to hunt for sunken vessels. Though he never actually saw the ad, James “Doc” Radawski heard about the strange and exciting opportunity in the far away land of Roatan from a friend. Having recently lost his job and truly sick of the California freeways, he applied and was accepted. And so his journey began. A DC-3 from Los Angeles to Mexico City (layover for the night), a DC-3 from Mexico City to Tegucigalpa (layover for the night), a DC-3 from Tegucigalpa to San Pedro Sula (layover for the night), a DC-3 from San Pedro Sula to La Ceiba (landing on a grass field specifically for The Standard Fruit Company) and finally a DC-3 to Roatan landing on the beach between houses and palm trees at the site of the current airport. It was 1970 and as with Mick, Doc’s life was about to change forever. He also never left the island.

There were no roads then, just a jeep trail from Coxen Hole to Paul Adams’ nearly completed Anthony’s Key Resort, still thriving to this day. Doc needed to get to Oak Ridge and learned that the only way was on the “mail boats” that ran every other day except for Sundays. Unfortunately, the day Doc landed the mail boats were off duty, so another layover in Coxen Hole. At 6AM the next day, Doc flagged a boat and got a ride to Oak Ridge via French Harbor, French Key Settlement and Jonesville. The final stop was at the Happy Landing Bar in Oak Ridge and a quick search for Mick. He was not hard to find.

The Santa Maria sank in the hurricane of 1969, so Doc only heard the stories. Prior to his arrival, Mick had secured a floating base for the mission, a 100 ft converted minesweeper out of French Harbor, complete with living quarters and laboratories, aptly named “The Rambler” along with a 30 ft x 18 ft barge on which to launch the explorations. Doc was impressed. Doc was also quickly caught up on the protocol of the search, mainly that The Rambler was required to have a Honduran soldier aboard at all times to be sure rules were followed and that Howard Jennings, still living on the island, did not like the Rambler’s presence. The Honduran soldiers were changed on the monthly basis as it was suspected that the newly permitted gringos would corrupt a particular individual if treasure was found, and Jennings did his best to disrupt the newest archeological expedition. It is reported that at one point, when The Rambler and the associated barge were anchored in the waters in front of Jennings’ land, he promptly came out to ask how long they intended to stay. Without a satisfactory answer, he returned to shore only to come back in his speed boat with a large knife in hand, a .38 pistol in his back pocket and began to cut the anchor rope. Doc had a picture, but it has been lost in the years. Needless to say, the expedition gained energy and devotion.

Mick and Doc immediately hit it off and the exploration was in full swing. They lived and worked aboard the Rambler searching with only islander stories and a magnetometer, a scientific instrument used to measure the strength and direction of the magnetic field associated with iron artifacts in shipwrecks. The team actually modified the instrument to upgrade it to a prototype gradiometer which increased the performance and then used the magnometers in pairs to better locate the wrecks, eliminating small interferences. Present day gradiometers are considered the most sensitive and reliable magnometers.

Over the next three years, their efforts revealed ten wrecks, all apparently either Spanish or British most likely from the 18th century when battles between the two nations for the control of Old Port Royal were common. Eight of the wrecks were unreachable due to the depth of their position, some as deep as 90 feet. Without the proper recompression equipment on the island, it was (then) considered too dangerous to go down that deep risking the bends and possible death. Fortunately two wrecks laid in 15 feet of water, thanks to the lowering water levels surrounding the island over the past 200+ years. And thus, excavation began.

The Rambler was outfitted with a dredge pump with capabilities to handle 4, 6 and 8 inch suction hoses. Unlike most wreck sites where remains and relics can be scattered over as much as half a square mile or more, these two wrecks were relatively intact thanks to the fact that they laid within Roatan’s protective barrier reef with provailing winds and tiny grains of coral sand acting as a natural preservative. The water conditions were ideal, clear and warm and without interference of hearsay treasure hunters due to the isolation of the island. Work commenced and findings became a daily occurance, some mundane, some amazing and some literally mind boggling.

Between 1740 and 1780, the British and the Spanish battled for control of Old Port Royal as it was a major colonial port. It was easy to get in and out of, had running water year round, could be easily defended and was a good place to do repairs on ships. One of the reachable wrecks, named PR4 ( Port Royal Find #4), looked to be a victim of one of the battles. The wreck was strongly believed to be British due to piping found on board and the mast and rudder sheathed in lead, rather than copper, which was not implemented until after the American Revolution of 1776. Doc recounts a story, supposedly originating from Roman times, that a coin was always placed under the main mast of a ship during its construction as a harbinger of good luck. The base of the mast on this particular wreck was still in place and thus the coin should have been there. The mast was carefully removed but there was no coin. Perhaps that was the problem – Doc says with a smile.

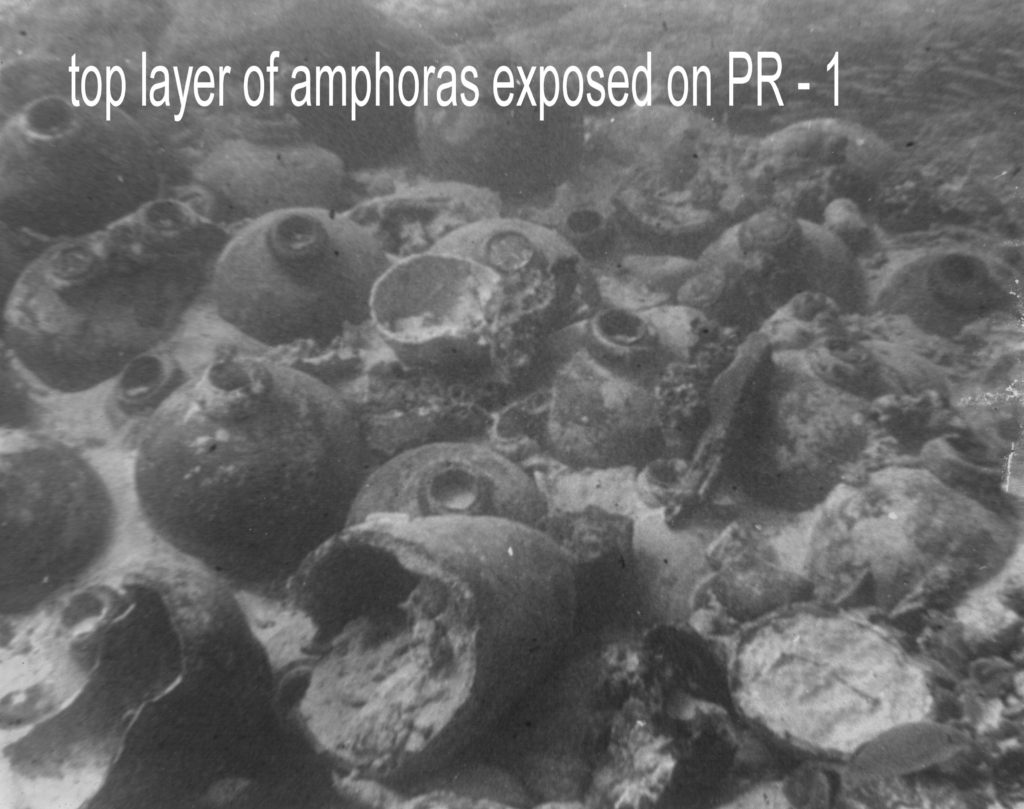

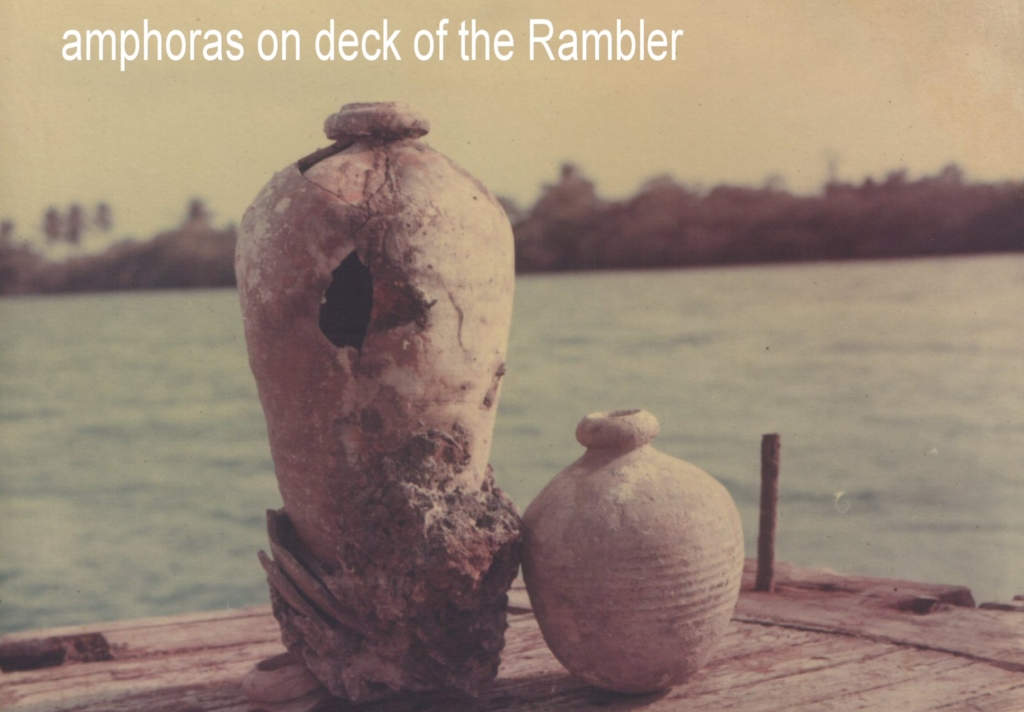

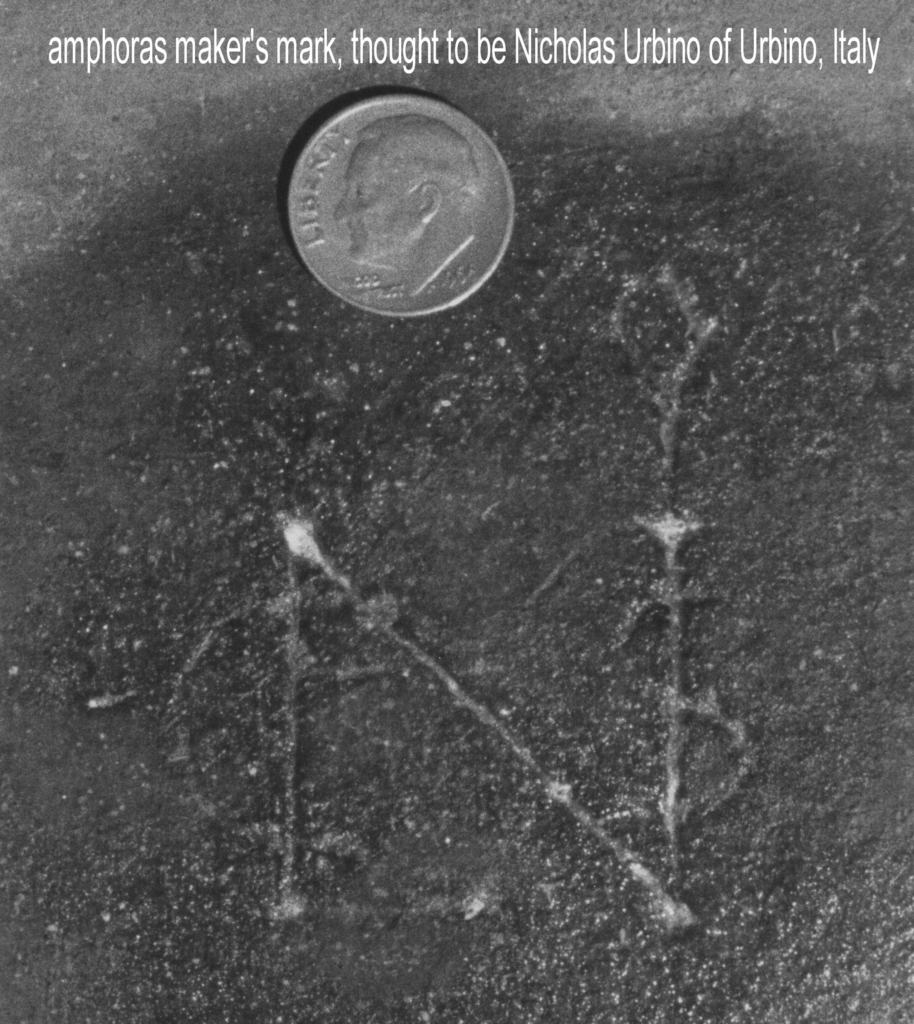

As fascinating as the finds on PR4 were, PR1 proved to be a whole different animal. Doc describes the discovery as something out of this world. When the PR1 wreck was initially spotted, Doc could not believe what he saw. The ribs of a thirty seven and a half foot wide ship lying quietly on the sand like a prehistoric dinosaur, perfectly intact in 15 feet of water. Excavation on this site initially indicated it was of Spanish origin due to the rudder design. The ship appeared to have sunk in a non-violent manner, upright and undisturbed. In the bow, lying like eggs stacked in crates, were over 40 amphorae, or Spanish olive jars, as if they were still waiting to be off loaded. It was the largest collection ever discovered on a shipwreck in recorded history. All were removed and carefully brought to the surface. One of the first things the team noticed was that some of the jars had been carefully repaired with tar. A quick test revealed that none of the ones intact leaked and that the volume of each of them was 15 liters within 2% error, an incredible feat, considering their suspected age. Clearly handmade with a curious maker’s mark on the bottom, a new investigation began. One of the team (now the expedition was employing a growing number of divers) traveled to Italy to see if their suspicions were correct, that the mark belonged to one Nicola da Urbino in the Italian town of Urbino. They found that, in fact, he did produce fine china, but not amphorae, from 1476 until 1526. A curious dead end though it is well known that such marks were copied and reused over the years. The next step was to have them dated.

Eight shards of the amphoraes were sent to the University of Pennsylvania for analysis. An infrared spectrophotometer found residue inside the jars indicating a material to be an ester of wood rosin , a natural stabilizer additive used to keep oil suspended in water preserving the oil. The shards were then tested using a technique called thermoluminescence dating, a method used to determine the date of firing in ancient ceramics, thus the age. When the piece is originally fired, all stored energy is released and the build up of new energy begins again. If the piece is then reheated to the firing temperature, the amount of rebuilt energy is again released as light and can be measured. Accuracy is usually around +/-5%. The actual test results on the jars were astonishing. The amphoraes excavated from PR1 wreck site were dated to have been manufactured in 1200AD, 300 years prior to the claimed European discovery of the Bay Islands by Columbus in the year 1502. The results were supported by Goggins Classification, a paper published in 1960 dating ancient ceramics by John Goggin, former professor of archeology at Yale University. Goggins Classification places them to the middle age between 500AD and 1500AD. If these results were absolutely correct, the Oceanograficos de Honduras had made one of the greatest discoveries in marine archeology history.

In 1200AD, the Spanish peninsula, then known as Iberia, was ruled by Muslims, known a fierce warriors and expert sailors. Were they crossing the Atlantic and trading with the inhabitants of Roatan? Were the inhabitants of Roatan an outpost for the Mayans? Or perhaps the Vikings traveled much further than their reputed landings in North America. Maybe it was the Chinese, also reported to have sailed the world long before Columbus. The possibilities required more investigation and Doc knew it.

One night, Doc was having dinner with his friend, Eric Anderson, and a girl called BJ whose boyfriend was visiting from Washington DC. Doc was telling the story of the PR1 finds, and the boyfriend suggested contacting National Geographic. I wish I could, replied Doc, but where do you even start? Simple, answered the boyfriend, I have lunch with the president of the magazine every Tuesday and I will tell your story. Six months later, Doc’s phone range. He had to be in DC the next morning, National Geographic wanted to speak with him. And so, he went.

Needless to say, the president of one the most prestigious historical and archeological magazines was extremely excited and intrigued by the findings at the wreck of PR1 in Old Port Royal. Grant papers were presented to Doc, filled out and submitted. The plan was to spend some time at the two major nautical history archives in the world: The British Museum in London and the Archives of the West Indies in Seville, Spain.

With the $25,000 grant from National Geographic approved and on the way, Doc and Mick presented their findings at The 6th International Conference on Underwater Archaeology in Charleston, South Carolina on January 7th 1975. There was a buzz of extreme excitement in the air, but, the buzz was quickly silenced.

For reasons that can only be self explained, the project was shut down and permits revoked. And that was the end. The crew, including Doc and Mick, dispersed. Most left the island and few are alive today. No one knows what became of Mick, but Doc presumes he is dead. As to the location of the wrecks, well, only one person knows that and though he has been approached many times to return to the sites, the answer is simple: not without a permit.

At the time, the future plans for the project included another five years of exploration and excavation. A new 105′ ship had already been purchased after The Rambler had rolled over and sunk in the 1972 hurricane. Land had been purchased to create a marine sciences field research station. Groups from the University of Miami and Northern Illinois University had already signed up to visit and contribute. All would have been a tremendous benefit to the island of Roatan not only for the historic importance but also for the ensuing tourism trade. Obviously, the time was not right. Perhaps it is now.